Japan's East Asian Security Challenges (Part 2)

Japan is facing numerous challenges internally as well as with its neighbours in East Asia. Japan is left to deal with the challenges of the region as well as ensure its own sovereign integrity. Japan seeks to find solutions for these challenges and provide a response to the future of the region. The following commentary is the latter half of a two-part series that explores Japan's security challenges in East Asia

Commentary (Part 2 Of two-part series for April 2021)

By Jay Maniyar

This commentary is a part of the series by the author, which explores the challenges Japan faces in East Asia and the larger Indo-Pacific region. The first part of the series can be explored here.

JAPAN AND EAST ASIA – DEALING WITH CHALLENGES

Japan remains severely restricted in the use and deployment of armed forces to protect national sovereignty and security. While Tokyo maintains a state-of-the-art military, the term 'military' is considered an aberration considering Japan's principled and determined anti-militarism philosophy. Instead, what it maintains is a 'self-defence' force that serves as Japan's unified military force, established by the Self-Defense Forces Law in 1954. Anti-militarism was institutionalized into the postwar domestic set-up through various laws, including a constitution that renounces war and a ban on dispatching military forces overseas. Nevertheless, Japan remains well-equipped—barring the nuclear sector as it has a policy against manufacturing, stationing or transiting nuclear weapons—with the professed aim to defend Japan from external threats rather than for offensive purposes. Such a posture is imperative to deter neighboring or external adversaries from venturing into Japanese territory/Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

However, within the limits of its self-defense, there is much that Japan can do offensively in the tense maritime domain of East Asia. Japan undertakes maritime patrols comprising land and sea assets that serve as preventive and preparatory mechanisms and are testament to the utility of Self-Defense Forces (SDF). Under the mandate adopted in the 1970s (early 1980s, as per a source), Japan is obliged to protect its sea lanes up to 1,000 nautical miles from its southern end. Military, especially maritime-naval and coast guard exercises in the East Asian region, is also a 'measure' being pursued vigorously by Japan, and in addition to ensuring defence preparedness and facilitating interoperability/understanding, exercises can serve to warn rivals, too.

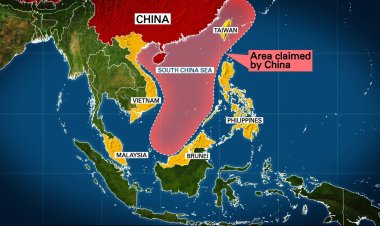

Japan also actively strengthens countries such as Indonesia and Vietnam in Southeast Asia with military assistance through sales and donation of necessary equipment. While this bears no (or possibly negligible) impact on East Asian security—it is an indicator of Japan's interests in the realm of defence as the principal means to achieve geostrategic goals. Through trade, interactive engagements, and participatory endeavours, military diplomacy is also a tool employed by Tokyo to win East Asia's contested (and crowded) strategic space. It is worth noting that, despite mutual respect and joint commitments, Japan can utilize every inch of the diplomatic space on offer to coerce its rivals into acceding to Japanese wishes. The country has amply demonstrated this in the protracted negotiations between Tokyo and Moscow over the Northern Territories (or the Kuril islands). Although all the four Kurils belong to Russia, Japan is keen on absorbing them into the main Japanese islands and has deemed their control by Russia as 'illegal'.

The direct and indirect threats posed by neighbors—such as North Korea, Russia, China, and even South Korea—Japan's posture is uncompromising. Territorial disputes, military antagonism with agencies such as the Chinese maritime militia, and the nuclear arsenal are just a few of the many Japanese security concerns in East Asia. These can be countered by demanding power, soft power or a combination of both. Japan is limited in the former and may not find much utility in using the latter for effective and lasting security threats. Hence, the challenges faced by Japan continue to remain as daunting as Japan's responses to them.

Is there more Japan can do in its immediate surroundings than what it is already doing? Certainly. Tokyo has come a long way in adopting postures that are more in tune with the changed regional geopolitics—straight arms exports relaxations to facilitate military trade with countries such as India, missions dealing with non-state actors that demonstrate Japanese operational willingness in the military arena, and the gradual adoption and timely up-gradation of its military by incorporating new technologies to augment existing capacities and capabilities. With cyberspace emerging as the latest domain of twenty-first-century war—Japan is all but accustomed to operating successfully to defeat its adversary decisively.

There have been increasing concerns over what is described as the "overt militarization" of Japan. However, it must be noted that today Japan faces threats from not just states but even non-state entities from the larger Indo-Pacific region. Since military power is described as the primary means for a state to achieve its geopolitical goals and diplomatic conduct, Japan has every right to continually broaden the contours of what it perceives to be 'self-defence'. Japan can, and must, utilize the strategic opportunities in East Asia, which are essentially the challenges on offer, to ensure its profile continues to gain strength as far as defence aspects are concerned.

Japan's fundamental approach in the military domain is transparent. It patrols its region extensively, has military assets and modern military technology deployed and positioned, and to deter threats posed by rivals such as North Korea, and continuously seeks to maintain a balance between defence imports and indigenization. It has acceded to a security relationship with the United States of America for several decades now premised on collective self-defense. This relationship also affords Japan nuclear protection in case its various possessions were to be attacked. Another additional advantage of the defence partnership with the U.S. is joint efforts in tackling combined threats such as that of a China-Russia or China-DPRK. Dealing effectively and efficiently with China in the East Asian domain is imperative for Japan, and given Chinese might, it cannot face the dragon alone.

In the non-traditional security sphere—apart from piracy and terrorism—Japan faces a formidable challenge in dealing with environmental challenges. Climate change, sea-level rise, the spectre of recurring natural disasters such as earthquakes and typhoons, and other such contingencies will require extensive policy-based, policy-focused, and policy-driven planning on Tokyo's part. This will have to take place well in advance, with the global agenda also in consideration for all humanity's betterment. Even the novel Coronavirus emergency has thrown Japan out of gear, and Tokyo is left to grapple with the ongoing pandemic, which has consumed innumerable Japanese lives while weakening its economic standing definitively.

JAPANESE RESPONSE AND FUTURE OF THE REGION

As can be ascertained in this two-part series of papers, Japan seeks to balance its investments in growing and sustaining the Japan Self-Defense Forces for the defence of Japanese islands with external security cover in the United States' form assuring presence. In doing so, Tokyo has ensured it does not compromise on the primacy of the SDF without disrupting its longstanding constitutional commitment to anti-militarism. In the same argument, Japan's pacifism is also balanced with the judicious employment of its so-called 'military'.

Defense White Papers issued annually by Japan's Ministry of Defense are concerned primarily with East Asian strategic space. Threats posed by neighbors remain at the top of the agenda of the policymakers. In the current geopolitical milieu of East Asia, Japan knows it cannot gamble with its defenses and is also aware that no matter how heavy, quick, and technology-oriented its defence improvement and modernization are, it will require the U.S. to secure it from a not-so-improbable combined threat posed by rogue adversaries such as Russia, China, and North Korea. Unresolved historical territorial disputes have caused immense fatigue within the East Asian strategic environs, and Japan knows this better than any other country. Their potential to impact interlinked sectors such as regional trade remains a realistic possibility.

As a principled nation, Japan also has a moral obligation to promote and propagate a lawful international 'rules-based order' in the high seas. Not only a protector, but it is also a driver of the rules-based system that was devised by former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, most visibly through a partnership with other 'like-minded' partner-countries in the form of Quadrilateral Security Dialogue.

Even the proposed Korean reunification plan may bring about unexpected geopolitical scenarios which may worsen Japan's overall fragile condition and pose new challenges that Japan never envisaged. Tokyo can no longer take the security of its neighborhood for granted or rely exclusively on the United States. Over the years, Japan has invested time, resources, diplomatic effort in developing a stable security environment for East Asia, but if it backtracks, it stands to not only lose its gains but compromise its territorial sovereignty.

This Article completes the two-part series of Articles for the Usanas Foundation on Japan's East Asian security challenges and concerns. The next series will focus on Japan in the Indo-Pacific region and pursue an approach similar to this one.

Jay Maniyar is a Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation, New Delhi, India. Mr. Maniyar is researching innumerable areas related to the maritime domains of Japan, the Republic of Korea, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the Indian Ocean and the Indo-Pacific regions.

Disclaimer: The views expressed above entirely belong to the Author of the Article, and any attribution of them to his employers, the National Maritime Foundation, and/or the Usanas Foundation are false.