Japan's Indo-Pacific Challenges (Part 1)

The following commentary looks at the issues and challenges presented by the complicated geography and geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific region concerning Japan. The article focuses on how Japan's Indo-Pacific strategy has evolved and how it can effectively tackle the problems faced by the nation.

Commentary (Part one of two-part series)

By Jay Maniyar

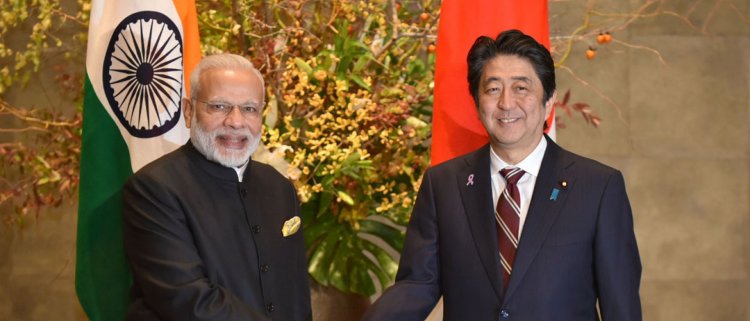

Japan’s Indo-Pacific (IPR) policy focus has been taking shape since the first announcement of a nascent strategy, more accurately described as a “vision” in the words of ex-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Officially called the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy (F&OIP)”,—this conceptualization of Japan’s Indo-Pacific vision, first made public in 2017, resonates well with its democratic and pacifist values enshrined in the Japanese constitution.

This approach is meant to deal with the issues and challenges presented by the complicated geography and geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific region—a vast terrestrial and maritime mass that houses critical countries, oceans, seas, straits/chokepoints, and sea lanes. It was exemplified in the words of Abe-san–where he eloquently referred to the IPR—as the “ confluence of the two seas.” This refers to the innumerable regions, sub-regions, and micro-regions marked by strategic proximity to the Indian and Pacific Oceans and are being viewed strategically and geographically as a single, united region.

The Indo-Pacific has, of late, gained much prominence owing to the bullish maritime attitude of the Peoples’ Republic of China, which has opened up the scope for cooperation, connectivity, joint infrastructure development, and resource development projects in this region with ‘like-minded’ partners. Thus, Japan has taken kindly to the region and has even repeatedly endorsed its partnerships in the Indo-Pacific to better understand many actors that find themselves discussing the future of the region all too frequently and for its greater good. For example, all of Japan’s Indo-Pacific partners (India and Australia) bear a synonymy to Japan’s benevolent vision and approach to the region.

Apart from the F&OIP, Japan agreed to the United States’ Indo-Pacific Strategy which is a grand cover for its Asian partners and other interested entities to help deal with the threat posed by an incredibly assertive and forthcoming Peoples’ Republic of China. Japan’s solicitation of so many Indo-Pacific entities is indicative of a country determined to seize the opportunity of the region and transform itself from a reluctant nation-state to a proactive one. However, to traverse these waters, Japan’s Indo-Pacifism finds itself surrounded by strategic challenges that will require attention and redress.

JAPAN’S INDO-PACIFISM: STRATEGIC CHALLENGES

Japan is likely to be compelled to figure its East Asian infestations as a small but significant part of its Asian outlook. Before Japan’s wallop to the Indo-Pacific, the secluded country viewed its security concerns solely from the prism of its nearby. To be fair to Tokyo, it was essential at the time because of historical discord with South Korea, the direct threat posed by an insecure and rampant North Korea chiefly through its missile programs, geostrategic tensions with Russia, and the focal East Asian menace posed by communist China.

The sheer length, breadth, depth, and width of the Indo-Pacific region are firstly indicative of Japan’s immense potential despite the interruptions of domestic factors such as legal non-militarism, population ageing, and a stagnant economy. The Indo-Pacific is a new adventure for Japan because its forces—a key component of any strategy abroad (even economic)—are legally declined to participate globally as part of Japanese post-1945 self-interest. The challenge, as they say, begins at home. In Japan’s case, a fundamental reform of the anti-military Constitution of May 1947 has been eternally pushed by the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) but remains distant. The LDP, traditionally pro-reform, appears disinclined to encourage Japan to pursue all-out, ‘normal’ military behaviour in the Indo-Pacific. This is due to Japan’s desire to portray an internal unity concerning Article Nine, outside differential political lines.

Meanwhile, Japan is utilizing every opportunity presented through interpretations of the controversial Article to broaden the scope of its internal strategic thinking concerning military normalization. Trade of maritime equipment with Southeast Asian countries is on the rise, and Tokyo is often found donating vessels to circumspect partner navies. A deal with its fellow middle power, India, for indigenous Japanese amphibious aircraft has also been touted for the longest time known. This amplifies Tokyo’s slow but steady determination to reform its 1947 Constitution. Military trade originating from Japan and intended to benefit countries dealing with traditional and non-traditional threats remain high on Tokyo's agenda.

With the Indo-Pacific stretch as far as East Africa's shores, Japan’s concerted involvement is faced with innumerable localized regional challenges. In East Africa, the Japanese have deployed anti-piracy missions to deal with the scourge of illicit activity and assist decrepit nations of a very long coastline. Sea piracy remains a matter of concern, with 38 incidents having been reported as of mid-April 2021. Further, Japanese and other merchant vessels' safe transit and holistic security are also critical challenges that require particular attention from Tokyo’s Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force (JMSDF). In this regard, Japan appears to openly challenge its anti-militarist frame of mind across the board through long-term security deployments ashore. That being said, Japan has been subjected to the pirate threat on several occasions and finds itself in foreign places due to its inadequacies in threat mitigation even ahead of infringements on local interests.

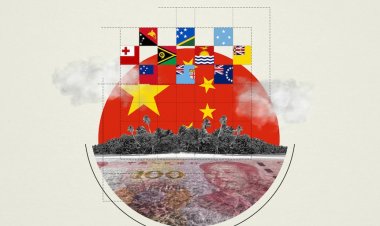

Generally, Japan also has to deal with the overarching threat of the Peoples’ Republic of China, with the security umbrella of the United States increasingly being seen as supplementary rather than dominant. China’s maritime shadow across the South China Sea, the East China Sea, East Asian waters, the Indian Ocean, and the East Africa-West Asia area is of immediate concern to Japan. This is primarily because of Japanese strategic interests coinciding with what may also be viewed as China’s envisioned areas of future geopolitical dominance. Already, China is a force to reckon with as it has obtained innumerable ports, constructed islands in strategic locations, and is fully determined to materialize the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in consonance with encirclement strategies meant to decapitate the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue’s (QUAD). Japan is also left to tactically fend for itself (except in the military-nuclear realm) in the Indo-Pacific with blatant, extensive, and expansive Chinese maritime ever manoeuvres taking place regularly through several agencies such as the Navy, Coast Guard, and a maritime militia.

On the challenge of nature—to which humanity finds itself in permanent distress—Japan’s immediate neighbourhood in the Indo-Pacific remains on edge as far as the possibilities of natural disasters are concerned. Even after the Fukushima Daiichi destruction of March 2011, Japan has witnessed havoc-wreaking disasters of all kinds. Japan is heckled by innumerable natural disasters every year, with earthquakes alone two to three times a day. These unfortunate occurrences range from earthquakes to typhoons (cyclones). Moreover, Japan’s well-minded material assistance to affected nations far away from East Asia is also a security challenge in itself as far as Japan’s outlook of the Indo-Pacific is concerned, as it demands considerable commitment on Japan’s part during difficult times.

CONCLUSION – JAPAN IS STIFLED BY THE INDO-PACIFIC CHALLENGE

Regarding the many challenges described above, Japan’s meek post-1945 international outlook stands to benefit as it evolves decisively. This is because Tokyo is now poised to set out to achieve what it grandly announced a few years ago and interlink its principled aims and objectives to on-ground actions and imperatives. It is a matter of wonder that Japan’s Indo-Pacific approach runs parallel to and will help deal with exactly the types of challenges the region faces. Beijing’s covert involvement across the region and its non-acknowledgement of the validity of the Indo-Pacific is strategic in conformity. It serves as extra motivation for Tokyo to set out to achieve what it wants.

It remains to be seen how Japan’s operationalization of its Indo-Pacific approach takes shape in the upcoming years and decades. Because of a sour cocktail of domestic constraints coupled with severe economic losses piled upon Tokyo by the damaging novel Coronavirus, the East Asian power is likely to find itself routinely assessing prevalent and new strategic challenges. A coherent Indo-Pacific strategy will only serve Japan well in addressing each of those challenges, and Japan is inclined to find itself well-suited to emerge as a key Indo-Pacific power.

Part 2 of this two-part series of Articles will address what Japan has been doing so far in dealing with challenges and how Japan can attempt to deal better with these strategic challenges in the Indo-Pacific.

Jay Maniyar is a Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation, New Delhi, India. Mr Maniyar is researching innumerable areas related to the maritime domains of Japan, the Republic of Korea, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the Indian Ocean and the Indo-Pacific regions.

Disclaimer: The views expressed above entirely belong to the Author of the Article. Any attribution of them to his employers, the National Maritime Foundation, and/or the Usanas Foundation is false.