China's Indian Ocean Challenge

China’s Indian Ocean presence is faced, from its point of notice, with innumerable, daunting, and unpredictable scenarios that bear the potential to challenge its fundamental supremacy across all other regions and the world. China is surrounded by a host of unaccommodating scenarios such as increased naval activity by China challengers in the Indian Ocean and India's increased claims to the space being its own.

Analysis

By Jay Maniyar

China In the Indian Ocean – Pursuing Several Interest

The Peoples’ Republic of China is an Indian Ocean power in basic terms while it works towards creating a broader presence and encapsulating the entire region within its strategic considerations. While it doesn’t yet purport to a massive presence in the Indian Ocean region, it has included the world’s third-largest water-body as central to its grand strategy. The Chinese approach to regions abroad has involved a proactive outreach to carefully and shrewdly identify countries where it can provide financial assistance, facilitate extensive local development, obtaining key stakes in the progress/rise of the countries being pursued, and integrating them within Chinese strategic thinking.

The Indian Ocean, in this context, matters immensely because it includes the vital arteries that are responsible for the unimpeded transit of energy to the Peoples’ Republic. China depends on the Arabian and Persian Gulf regions for a majority of its energy derived from non-renewable sources. The Indian Ocean also lies at the heart of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a massive infrastructure-connectivity program funded and furthered by Beijing through its own might.

In the present circumstances, China’s Indian Ocean involvement has been marked by a strong sense of self-interest coupled with a keen eye on fostering regional development attuned to the benefits of partner countries and inclined to manufacture a China-dependency. The Indian Ocean has afforded immense strategic opportunities to China which it has willingly pounced upon and furthered its regional and global agenda through a multidimensional strategy. The world’s third-biggest oceanic space suits China and accords it ideal conditions in which to go about trotting Asia and make its mark on the Indo-Pacific region.

What China is doing in the Indian Ocean ranges from information gathering and sea surveys for potentially valuable material resources to transiting the area in missions to live up to its commitments to regions such as East Africa with a clear and visible Chinese presence. An extended interest of countries such as the United States and Japan in even proximate Indian Ocean regional zones such as the Bay of Bengal on India’s eastern seaboard is also possibly because of China’s strategic shadow over South Asian land and sea and the frightening possibilities of confrontation and conflict between big players.

What exactly is this presence being given shape and direction by President Xi Jinping that must also be geared to combat the many challenges on the Indian Ocean table? China has partnered with countries such as Sri Lanka and the Maldives to achieve its end-goal of strategic domination of the Indian Ocean. This partnership is marked mainly by headline infrastructure projects meant to boost connectivity and stimulate trade and commerce across the high seas. This is being undertaken largely thanks to the playing hand of China’s financial might across Asia and the world. In Sri Lanka, China has obtained a US$ 1.1 billion lease of the Hambantota port for close to a century, since 2017. It has been said that a second 99-year lease was also on the table but was denied officially by China. The Feydhoo Finholhu atoll of Maldives was leased by China for 50 years in 2016 for a meagre US$ 4 million. As per a Eurasian Times report, China has leased more than one island of the Maldives which explains increasing Chinese land resources, a phenomenon that has taken place in the South China Sea waters.

Even in Indian Ocean-annexe regions such as the Arabian Sea-Persian Gulf interface, China is working hard and with a sense of unprecedented ferocity in its dedicated approach. Pakistan’s Gwadar port is the lynchpin of the anti-India China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) while it is constantly on the hunt by bulking its ‘String of Pearls’ strategy through shrewd acquisitions of maritime assets. These could be atolls, islands, and port infrastructure. The Chinese strategy, hence, appears holistic and interest-driven.

China's Indian Ocean Challenge

As far as the Indian Ocean is concerned, China is faced with a challenge despite its legitimate claims to being an Indian Ocean power well ahead of countries such as Japan, the Republic of Korea, Australia, and even India to an understandable extent. China’s derision of India’s Indian Ocean claim (that the Indian Ocean is India’s own, owing not just to geographical proximity but even a historical connect) is somewhat rightly attributed to an active Indian Ocean and IOR-wide foray by China that tends to overawe India on occasion. The Indian Ocean is Asia’s most important strategic area (even for China as it is the passage for Beijing to Africa and Indian Ocean countries as also friendly South Asian countries) that is witness to geopolitical competition on an immense scale and a plethora of prevalent and emerging interests within its confines.

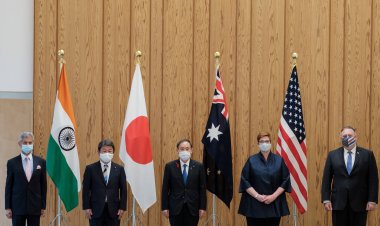

However, with the Indian Ocean region emerging as a geostrategic entity on its own standing in comparison to the prioritised Indo-Pacific and with the Indian Ocean at the core of this welcome development, China will be increasingly challenged by countries such as Japan, India, Australia, and a determined United States of America’s Asian avatar under its new 2021-24 administration. This refocus to the Indian Ocean by a number of countries, to rephrase a borrowed policy in the US rebalance to the Asian continent in the early 2010s, is the greatest challenge China faces. The reason for this is the sheer all-round potential conveyed by these countries in not just outcompeting with but even outdoing China in the Indian Ocean.

Yet, China remains stubborn and resilient in the wake of a potential confrontation with major powers that are all but an Indo-Pacific alliance by themselves and formal organisations such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) of four Asia-Pacific nations. Chinese rigidity in the case of the Taiwan issue has been a defining characteristic of its great power ambitions and has led to the US having prophesized aggressive overtures by Beijing towards Taiwan within the next six years.

Conclusion – Unaccomodating Scenarios

China’s Indian Ocean presence is faced, from its point of notice, with innumerable, daunting, and even unpredictable scenarios that bear the potential to challenge its fundamental supremacy across all other regions and the world. An unstable and volatile Indian Ocean can impact China’s economic rise and its energy dependency on far away but strategically-proximate regions such as West Asia. Even the Chinese presence in the western Indian Ocean region is subject to an impact from the many challenges at hand in the Indian Ocean. The contest for China includes having to face traditional, non-traditional, and other challenges that can surface from the realm of unpredictable events.

In summary, China is surrounded by a host of unaccommodating scenarios such as increased naval activity by China challengers in the Indian Ocean and India's increased claims to the space being its own. However, its strategy is devised on weathering the facing storm and eventually emerging as an unequivocal winner with all challengers brushed aside and all challenges conquered. The Indian Ocean offers a still-rising China exactly what it has been seeking not just in terms of material gains but to eventually utilise any available medium and a maritime one such as the Indian Ocean itself, to finally usurp the United States to global superpowerdom.

Jay Maniyar is a research associate at National Maritime Foundation.

Disclaimer: This paper is the authors' individual scholastic contribution and does not necessarily reflect the organisation’s viewpoint.