Japan's Indo-Pacific Challenges (Part 2)

The following commentary looks at the issues and challenges presented by the complicated geography and geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific region concerning Japan. The article focuses on how Japan's Indo-Pacific strategy has evolved and how it can effectively tackle the problems faced by the nation.

Commentary (Part two of two-part series)

By Jay Maniyar

This article is the second part of a 2 part series exploring the complex geopolitics of Asia-Pacific. Part 1 of the article can be accessed here.

JAPAN IN THE INDO-PACIFIC REGION – ASSESSING INVOLVEMENT

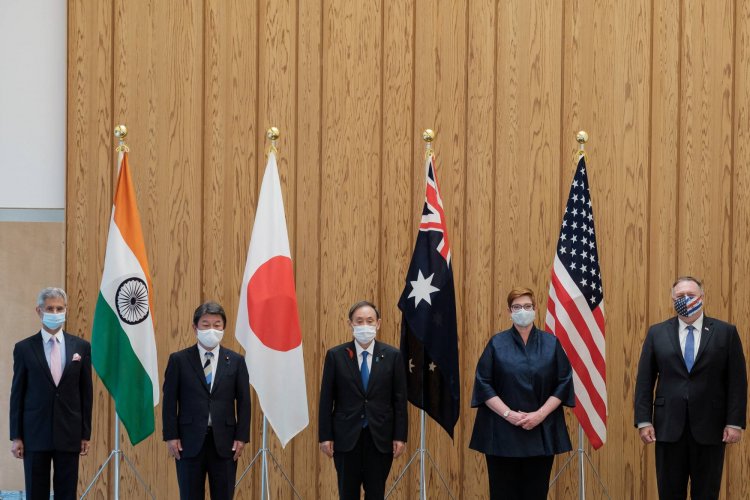

Japan is an ambitious Indo-Pacific country—one that is ahead of the strategic curve. A formal and articulate enunciation of an Indo-Pacific policy has taken place at the behest of Tokyo’s leaderships. Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe led the way by calling for an outlook on the region that was unprecedented in post-WWII Japanese history. His successor, the incumbent Yoshihide Suga, has carried forward his optimism and furthered the Japanese cause in the Indo-Pacific. However, it remains short of grand pronouncements such as Abe’s ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ vision. With Suga being seen as a liability in the face of his low approval ratings due to the inefficient handling of the novel Coronavirus, the way Japan’s stance on the Indo-Pacific region evolves remains to be determined. It remains to be seen how, outside political lines, Japan behaves strategically in the Indo-Pacific both for its self-interest and its wider regional interests.

In summary, Japan’s involvement in the Indo-Pacific region is that of a pacifist actor keen on assuming more responsibilities while stressing upon a rules-based and free order in the seas and oceans of the region. David Brewster has suggested that Japan take forward its overarching interest in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) by emphasizing freedom of navigation in the world’s third-largest oceanic body—the Indian Ocean. Japan’s geopolitical, geoeconomic, and geostrategic interests are best served by active involvement in the peace and strategic stability of the Indo-Pacific as enunciated in its “Proactive Contribution to Peace” concept. Further, a sustained interest in the region and active involvement with partners will build stubborn alliances in and around the Peoples’ Republic of China (PRC) and curtail its dominance in this key interface.

This article briefly delves into Japan’s approach to the strategic challenges by a strategically volatile Indo-Pacific. The challenges are innumerable, but they are also increasing in number, depth, and magnitude; thus, while Japan is all set to be involved in a region where the challenges can be overcome only through sustained, long-term involvement, participation, a commitment of national resources, and an unequivocal endorsement of the approval of the Japanese people.

OVERCOMING STRATEGIC CHALLENGES – JAPAN AND ITS SECURITY

Japan is faced with innumerable strategic challenges ranging from being handicapped by domestic legislation on national defence and constitutionally embedded restraints to dealing with the burgeoning threat posed by China. While legal reform remains pervasive, Japan continues its liberalization of defence policy, albeit slow, to further its broader strategic ambitions. Such a development is a step in the right direction, as Japan’s neo-cooperative avatar can decisively stiffen partner nations who appear to be weaker outside the frame of such mechanisms.

As far as the threat of sea piracy is concerned, Japan’s freedom in the high seas remains severely constrained and has been perennially tested. In the Arabian Gulf peninsular region, Japan has undertaken rotational deployments to stem the threat. In Southeast Asia, Japan provides indirect assistance to curb the piratical threat through donations of naval patrol vessels (either donated directly or provided for through financial assistance to facilitate their production domestically) and regional foresight. Thus, Japan remains at the helm, and despite military restrictions, of the Asian fight against maritime piracy for the better interests of the Indo-Pacific.

Japan is also a provider of humanitarian assistance, aid, and relief to combat security challenges presented by natural forces, which result in widespread losses of people and property. In the western Indian Ocean region, Japan has been involved, apart from sea lanes security for safe transit of merchant ships, in mitigating disasters such as the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and Cyclone Nargis (Myanmar, 2008). Overall, this critical segment of the Indo-Pacific region remains on edge as far as the fury of natural events is concerned. The challenges posed by these non-traditional threats to the maritime security of the Indo-Pacific may be faced with Japan as a formidable player capable of exercising its expertise and experience in handling such crises.

The October 2018 meeting between Shinzo Abe and President XI Jinping in Beijing had a decisive influence on regional geopolitics. It indicated that cooperation and congruence (wherever feasible, such as with the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) remain on a table, alongside confrontation and conflict. This could bode well for the Indo-Pacific region from a few specific viewpoints, such as an affable China. A likeable China will likely set the tone for future leadership in the region, given its immense clout that continues to multiply in scope and possibility every day. Japan will welcome such a development as it could potentially result in a peaceful resolution of all territorial issues in the region while preserving healthy economic ties.

Despite some of the lesser-known cooperative aspects between Japan and China, as highlighted by the French scholar Celine Pajon, overarching concerns relate strongly to a situation of tumult and turbulence. China’s ignorance of the Indo-Pacific creates confusion in the Japanese psyche about its intent. This is because a majority of Chinese initiatives these days have been put forward in this geostrategic region. Further, a threat by the Chinese of the nuclear annihilation of Japan resulting from Tokyo’s masculine approach to the Taiwan issue casts the Japan-China relationship in the Indo-Pacific in poor light.

CONCLUSION – JAPAN IS HERE TO STAY IN THE INDO-PACIFIC

Despite daunting prospects and difficult challenges, Japan has already attuned its strategic posture to a decisive Indo-Pacific power. Tokyo’s promulgation of a ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific' is strong, meticulous, and applied. The region has already witnessed a ton of Indo-Pacific ventures, courtesy of Tokyo, which have been wholeheartedly endorsed by regional players who view Japan as a previously reluctant nation now willing to expand its role prudently. These include boosting infrastructure connectivity all across the region, working towards maritime security unilaterally and multilaterally, and building partnerships with India, Australia, South Korea etc.

All of the above offer ample evidence of why Tokyo would be willing to face security challenges determinedly, even by itself. For a long, it has been suggested that Japan must overcome its reluctance to become a ‘normal’ power and embrace a broader role. The problem may be that ‘normalcy’ (of the type recommended for Japan) brings with it that strategic complications can subdue regional actors in the long term in the present international environment. With the strategic rise of the Indo-Pacific imminent, Tokyo will be compelled to rethink some aspects of its Indo-Pacific strategy and become a country that doesn’t just participate in the region but even belongs to it.

Jay Maniyar is a Research Associate at the National Maritime Foundation, New Delhi, India. Mr Maniyar is researching innumerable areas related to the maritime domains of Japan, the Republic of Korea, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the Indian Ocean and the Indo-Pacific regions.

Disclaimer: The views expressed above entirely belong to the Author of the Article. Any attribution of them to his employers, the National Maritime Foundation, and/or the Usanas Foundation is false.