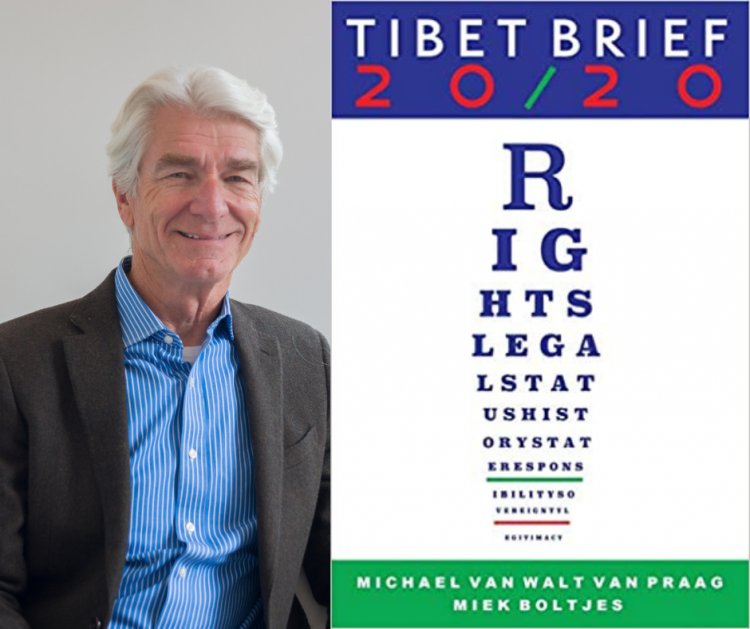

Tibet Brief 20/20 by Michael Van Walt and Miek Boltjes | Executive Summary

Contrary to what the People's Republic of China (PRC) claims and to what many people take for granted, Tibet was historically never a part of China. The outcome of our research removes any doubt that the PRC's presence in Tibet is unlawful. Tibet is an occupied country, and the PRC does not possess sovereignty over it. This calls for an immediate course correction to bring government policies in compliance with international law.

Tibet Brief 20/20 presents an examination of Tibet's historical relations with the dominant empires in Inner and East Asia with a view to establish who has sovereignty over Tibet today. It does so applying the norms of three pre-modern Asian legal orders as well as those of modern international law where and when they were applicable.

The historical situation is relevant today because—since the PRC bases its entitlement to Tibet solely on its allegation that Tibet has been an integral part of China since antiquity—it determines whether the PRC has the legitimacy to rule Tibet and exploit its resources.

Our research firmly establishes that contrary to the PRC’s claim, Tibet was historically never a part of China. Though not always 'independent' in the modern legal sense of that term and subject to various degrees of Mongol, Manchu and even British authority or influence, it was most certainly never a part of China. The PRC therefore also could not have 'inherited it' from the Republic of China or earlier empires, as it claims. As a matter of fact, Tibet was an independent state de facto and de jure from 1912 to 1950/51, when the PRC invaded it. This is highly relevant because it brings international legal obligations for both the PRC and all other states today.

Because Tibet was not historically a part of China, the PRC's military invasion of Tibet in 1950/51 constituted an act of aggression and violated the peremptory norm of international law prohibiting the acquisition of territory by the use or threat of force against another state. It did not, therefore, provide the PRC with legal title to sovereignty over Tibet.

The international legal characterization of the PRC’s presence in Tibet is that of the occupier. This brings legal obligations on the PRC pursuant to the law of occupation, in particular, to protect the population under its authority. But occupation, however prolonged, cannot confer sovereignty to the occupier.

The PRC did not acquire legal title to sovereignty over Tibet through prescriptive acquisition either. The PRC's presence in Tibet does fulfil the criteria of effective control under international law, but this is not sufficient. For the prescription to have taken effect, there must have been an absence of opposition or protest from the Tibetan government and people. The PRC’s possession must have been peaceful, and the underlying problem must have been genuinely settled. This book shows that none of these criteria has been met.

The PRC not only illegally occupies Tibet, but it also denies the Tibetan people their lawful exercise of self-determination. This denial, the PRC’s active opposition to any expressions of it, and its modifications of administrative boundaries of what are now the Tibet autonomous region, prefectures and counties, all constitute violations of fundamental norms of international law.

Both Tibet's occupation and the denial of the exercise of the right to self-determination are serious violations of international law by the PRC that impose duties on all other states. In essence, governments are obliged to:

not recognize the PRC's unlawful seizure and annexation of Tibet;

not render aid or assistance in maintaining the PRC's unlawful occupation;

not render aid or assistance in the PRC’s ongoing denial of the Tibetan people's right to self-determination;

endeavour to bring the unlawful occupation of Tibet to an end with the cooperation of other states; and

permit and respect the Tibetan people's right to self-determination.

Many states are today acting contrary to these obligations, in plain violation of international law and in disregard of the reality, namely that the PRC does not possess sovereignty over Tibet. Two developments stand out in this regard: governments make statements recognizing that Tibet is part of the PRC, and they treat Tibet as China’s internal affair, outside of their purview. Some who engage in trade also treat Tibet’s resources as if they were China's to dispose off. This has made governments accomplices or, at best, passive bystanders, whereas in fact, they have a positive responsibility to help end the occupation of Tibet.

When governments state that they consider Tibet to be a part of the PRC, they take away the PRC’s principal incentive to negotiate with the Tibetans as well as reduce the latter's main source of leverage. In the first place, Beijing uses these statements as ‘evidence’ for its claim that it has sovereignty and legitimacy in Tibet, and even for its historical claim. The more such statements it obtains, the less it feels the need to turn to Tibetans for legitimacy. Instead, it uses the international community’s pronouncements as a substitute for true legitimacy, that is, the legitimacy that would result from the consent of the governed—through an exercise by the Tibetans of self-determination or through a process of genuine negotiations. Secondly, once a government states that it considers Tibet to be a part of the PRC, it cannot but treat Tibet and Sino-Tibetan relations as China's internal affair. This is effectively happening today: most governments are self-censoring and satisfy their own constituents’ demands that they act on Tibet and pressure China by limiting their expressions of concern to human rights abuses. In this way, Beijing has largely succeeded in containing international scrutiny and reproach to where it can manage it.

Some governments have also added that they do not support or are opposed to Tibetan independence, making their statements particularly damaging because they not only violate the prohibition against recognizing illegal forceful annexation but also constitute a denial of the Tibetan people’s right to self-determination, an equally serious violation of international law. Even though states cannot actually take away the right to self-determination, including independence, from the Tibetan people, such statements do the Tibetans a great disservice and encourage Beijing to ignore the Tibetans' rights. By supporting the aggressor, not the injured, they also fail to fulfil the fundamental role international law requires the international community to play — to prevent war and promote friendly relations and cooperation among states based inter alia on the principles of non-use of force against other states and of equal rights and self-determination of peoples—, frustrating the very purpose of international law in the process. For, as the International Court of Justice underscored in the Namibia case, it is precisely to the international community that the injured people must look for ending the illegality and for realizing its rights.

It is for Tibetans, and Tibetans only, to make concessions with respect to their right to independence—if and when they so decide. Ruling out independence, as some governments have, one-sidedly disempowers the Tibetan side, weakening its negotiation position, thus exacerbating the already stark asymmetry and conditioning the expectations of the Tibetans as well as of the international community to envisioning a settlement that can bring only marginal change to Tibet.

The need for the international community to take responsibility and effectively address the Sino-Tibetan conflict is not just a legal and moral imperative, it is also a political necessity. Looking the other way with an underlying "let’s not make the Tibetans’ problem our problem" has been a mistake for which the international community is today paying a price as it tries to deal with an emboldened PRC asserting expanding territorial claims and influence. Beijing's reignited territorial claims in the South China Sea, northern India and Bhutan, its exertion of undue influence in Nepal and Mongolia, as well as its violations of Hong Kong’s guaranteed autonomy and mass incarceration of Uighurs, all taking place at the time of this writing, cannot be treated as unrelated to the years of international appeasement of Beijing as concerns its unlawful seizure and occupation of Tibet and its implementation of oppressive policies of integration and assimilation there.

In order to end the occupation of Tibet, certain things need to be in place, for which the international community’s engagement is imperative. The engagement called for is entirely in line with the legal obligations and responsibilities of states, does not constitute impermissible interference in the PRC’s internal affairs, but does require a significant course correction. This calls for states to:

Desist from stating that Tibet is part of China or the PRC. At no point in time did the PRC inherit or acquire sovereignty over Tibet. In fact, Tibet is not legally a part of the PRC today. Refraining from making such statements would be a first step to rekindle incentive for the PRC to obtain the legitimacy to rule Tibet from those who possess it, namely the Tibetans, and would bring governments in compliance with international law in this regard.

Refrain from stating that they oppose or do not support independence for Tibet. Not only are making such statements contrary to international law, but it also is not their prerogative to decide Tibet’s status.

Treat the situation in Tibet, Sino-Tibetan relations and the Sino-Tibetan conflict as falling squarely within the international community’s, and therefore every government’s purview and responsibility and not as China’s internal affair.

Endorse the Tibetan people’s right to self-determination, as called for in UN General Assembly Resolution 1723, and speak out against the denial by the PRC of its exercise.

Use language reflective of the true situation instead of adopting PRC terminology. Tibetans must be referred to as a 'people' and not a 'minority' or 'ethnic group of China.' The Tibetans are a people under international law, people under alien subjugation and domination. Adopting the PRC's terminology denies the Tibetan people its proper status and implicitly it's right to self-determination. Similarly, the use of euphemisms such as 'the Tibet issue' to refer to the ongoing occupation of Tibet and the Sino-Tibetan conflict is unhelpful: it diminishes the seriousness of the situation and hides the international character of the conflict as well as the international community's responsibility and obligations to address it.

Actively engage with both parties on (re-)engaging in dialogue and initiating substantive negotiations to resolve the conflict in ways that can satisfy the needs and interests of both parties. Persuade Beijing to enter into negotiations with the Tibetan leadership without preconditions and impress upon the PRC leadership that it can only be through that process or by means of a free and fair referendum that the PRC can achieve the desired legitimacy and resolve its conflict with Tibetans.

Reject the 'core interest' trap and with it the imposition by the PRC of rules of behaviour that dictate what governments must believe, what their officials must say, and who they should or should not meet and engage with. Be guided, instead, by facts and law, including international legal principles and norms.

Refrain from explicitly or implicitly endorsing the PRC's false and misleading historical narrative on Tibet, which is part of its annexation strategy. Importantly, accepting or not contesting this narrative also has repercussions beyond Tibet, since it validates Beijing's territorial claims in northeast India and impedes contesting related narratives deployed by Beijing to lay claim to other territories, such as those in northwest India, the South China Sea and the East China Sea.

Prohibit and sanction business arrangements that aid the PRC in maintaining, strengthening, entrenching or profiting from its presence and exercise of power in Tibet and its suppression of the Tibetan people’s right to self-determination.

Dr. Michael van Walt van Praag is an international lawyer, a mediator and advisor in intrastate peace processes, and professor of international law and international relations.